Torture and confession are like the ‘dark twins’ as Foucault said.

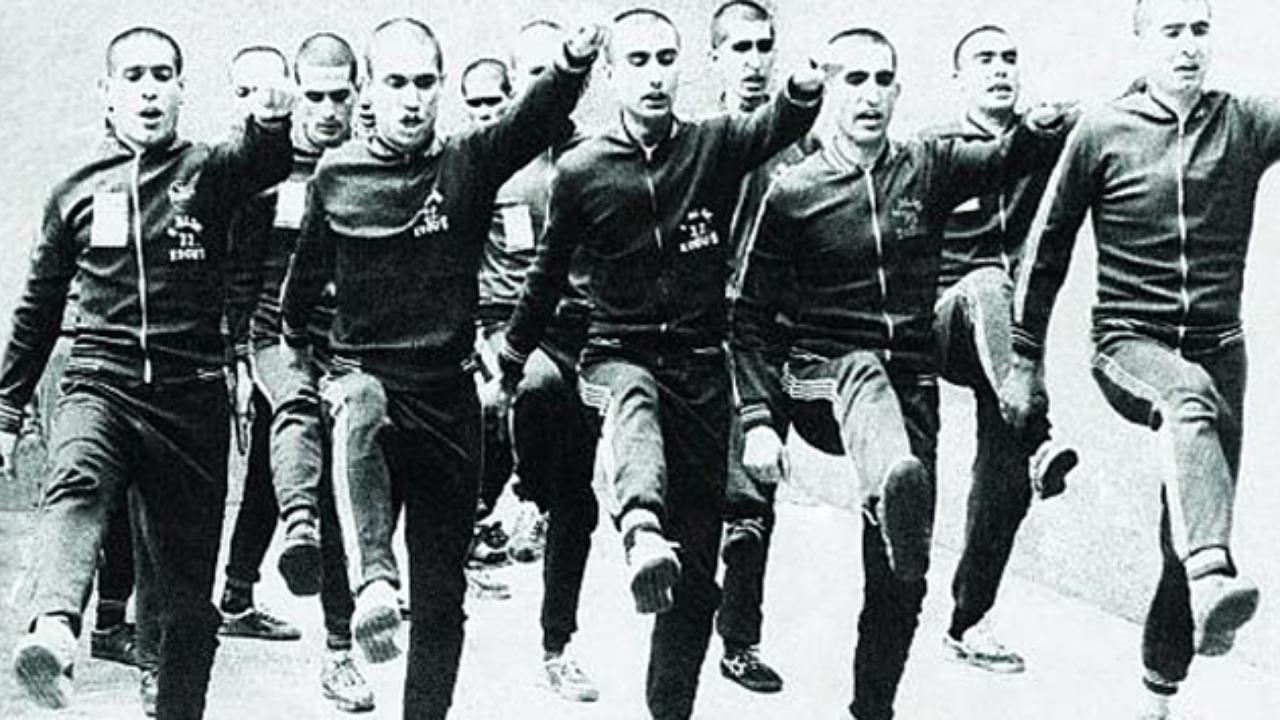

Definitions of torture from the Ancient Greece to the 21st century indicate confession as its primary motive. Whilst torture continues to be perpetrated by modern states for the purposes of punishment, intimidation, coercion and establishing control over the accused, obtaining information and confession is still used as the main justification for the widespread use of torture particularly during political conflicts. Successive Turkish governments have also systematically resorted to torture against Kurdish political activists to extract confessions. In this article, through an analysis of the case of Diyarbakir Prison in the early 1980s, I argue that extracting confessions from the accused does not primarily aim at securing convictions or obtaining accurate intelligence, but as a technique of discipline and control. Drawing upon scholars such as Foucault, Scarry and DuBois, I argue that confession functions as a ritual for recognition of the sovereign power and inscription of the official truth in the body of the accused. Confession is not only used to complement missing knowledge but to “fulfil the punitive system” by transforming the accused into an obedient self.